September 08, 2023

Hot Takes For a Hot Month

News Takes : Hot Takes | Our Take

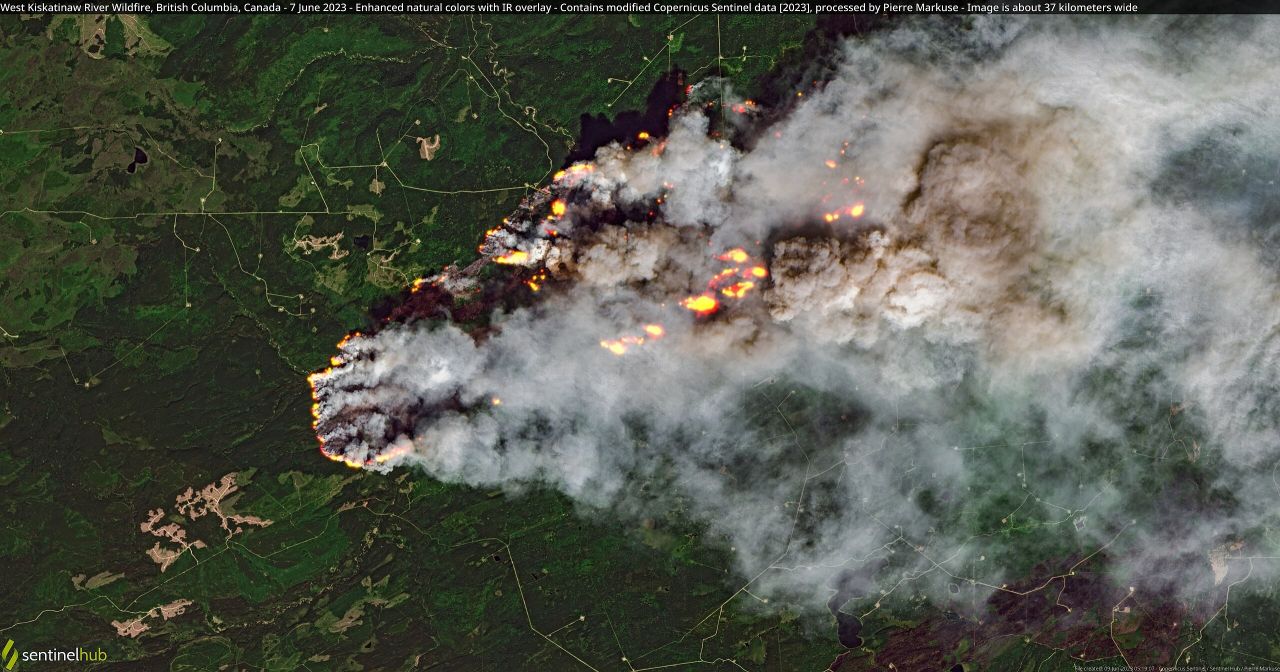

West Kiskatinaw River Wildfire, British Columbia, Canada. June 7, 2023

Credit: Pierre Markuse | CC BY 2.0Hot Takes

All through the month of August, news stories about the extreme heat were popping up like summer storms. July was the hottest month in recorded history, and the news on climate change was driven by severe weather events. In Las Vegas, following an almost unheard of hurricane hitting southwest desert states, two people went missing after being washed away by flashfloods. In Germany, despite extreme heat that has scorched much of Europe, one town had to get out the winter snowplows after a foot of hail blocked streets.

Where northern summer winds often spell relief for the lower 50, this summer they brought smoke as more than 25 million acres of Canada’s boreal forests burned due to a heat dome and draught that have been fixed for months. In Florida, Insurance companies will no longer cover coastal properties because the risk of damage from hurricanes fueled by bath water temperatures in the gulf is too great. Actuarial tables do not lie.

These are not normal times, yet though the extreme events made the headlines, the news on climate change has often followed normal way of covering the topic. For the American news media, this often means turning to data, not to climate data - which also does not lie - but to ambiguous polling data about what people say they believe.

In the US news media system, there is a strong tendency to turn everything into a political story and follow the story through the polls. It’s an old tendency, which dates back to the 1920s when people started conceiving of public opinion not as a vague index of general will, to be followed through large social movements or cultural trends, but as an objective social fact that could be measured through statistics. Political reporting is often driven by a new poll being released that shows the numbers going up or down. The problem is that instead of focusing on the stakes of politics for governance, poll-driven reporting turns everything into a horserace where reporters tie a news event to poll numbers and predict what could move them. The noise on the horserace drowns out the news about governance, which is a big problem for democracy.

Lately, the takeaway of most poll-driven stories is that Americans are divided along partisan lines. And everything and every issue that reporters write on, tends to be refracted through that monofocal lens.

So too with the news about Climate Change. Of the many hot takes during the hot month of August that refracted news about climate change through the lens of political polling to reinforce the narrative that “Americans are divided,” this one from Washington Post takes the prize.

“Democrats and Republicans divided on the causes of extreme weather, Post-UMD poll finds.” What does framing news about climate change this way accomplish? How does this help readers understand why temperatures are rising, what the stakes are and what we, as a democracy, might do about it?

Not much. We learn that “Partisans remain split on climate change contributing to more weather disasters,” but so what? The data about climate change is unequivocal, and aside from noise makers that the fossil fuel industry pays to muddy the debate in our news system, scientists are clear about what it means. Measurable carbon levels are rising and with it are measurable heat indexes, water temperatures and extreme weather events. But by reducing climate change to the standard story on public opinion polling, and providing quotes from representatives of both sides, readers just chuck this issue with other politicized issues and it’s easy for partisan skeptics to brush off climate science as mere opinion.

Our Take

It is not hyperbolic to say that this issue demands more from journalists. It is certainly true that democrats and republicans are divided on the issue. The Pew Center, whose public interest polling is impeccable, confirms that the repetition of industry-fueled narratives, which provide readers permission to ignore the news has worked. We know how important media diet is and that people believe the media they consume, so this is really not news. By turning everything into a partisan issue where we agree to disagree, news orgs are not covering climate change, they are covering it up.

We would like to see more reporting on where the sticky narratives and slogans that drive climate change denialism are coming from. Polling might be useful here if it helped show the cause of the climate change denialism by tying beliefs to media consumption. It would at least explain why so many Americans who consume right wing media believe narratives and talking points about climate change that are false.

Most climate denialism is driven by PR messaging firms that are paid to create the impression of disagreement. Politicians on the fossil fuel payroll take their talking points from these campaigns. Journalists should distinguish themselves from paid shills for the fossil fuel industry by calling out this paid disinformation so as to diffuse its power. There is no need to platform and amplify people who are part of the disinformation campaign.

That politicians, including all but one of the GOP primary candidates at the last debate, still echo climate change denialism does not change the data or the facts. Climate change is happening, and it is happening faster than most scientists imagined. But due to the impact of climate change denialism in our media ecosystem, governments around the world are not only failing to enact policies that will curb carbon emissions, but they are actually subsidizing fossil fuel extraction at record levels. Last year G20 countries poured more than $1 trillion into subsidies despite pledges to do the opposite. This is climate change news. That the public is divided about climate change is just a product of too much inadequate or misleading reporting on it.

Reporting about climate change should be about what is happening, why it is happening and what we can do about it. Anything else at this point is amplifying noise over news. — Matt Jordan