July 10, 2023

Much Ado About the Monied in the News

News Takes : Hot Takes | Our Take

Composite image. Original images: "Mark Zuckerberg F8 2018 Keynote" by Anthony Quintano is licensed under CC BY 2.0. "Elon Musk Royal Society (crop2)" by Debbie Rowe is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Credit: Creative CommonsHot Takes

You may have heard the adage, "there’s nothing new under the sun." When it comes to news organizations choosing which stories to cover, this still rings true today. While there were many noisy news stories in June, the noisiest - which is to say the story that had the least to do with providing citizen with information essential to the functioning of democracy - was the ongoing coverage of a potential “cage match” between billionaires Mark Zuckerberg and Elon Musk.

Like so much of what passes for news in our media ecosystem, the story began as a truncated social media post. On June 20, Elon blustered on Twitter, the social media platform he owns, that he would be up for a “cage match” with Zuckerberg. Zuckerberg responded on Instagram, the competing social media platform he owns, with three words: “Send Me Location.”

On June 20, Elon blustered on Twitter, the social media platform he owns, that he would be up for a “cage match” with Zuckerberg. Zuckerberg responded on Instagram, the competing social media platform he owns, with three words: “Send Me Location.”

Credit: Twitter, FacebookThat brief interaction between two of the world’s richest men launched a thousand noisy news stories as every news organization got in on the game. Within hours, USA Today, The New York Times, CNN, BBC, Variety, CNBC, The Washington Post, The Chicago Tribune, The Wall Street Journal, The LA Times, and many more all had headlines calling attention to it.

The New York Times publishes an article titled "Elon Musk Proposes 'Cage Match' With Mark Zuckerberg.'

Credit: The New York TimesBy the next day, the story was trending, and the “analysis” stories began. Sources and experts speculated about who might win and who would get hurt. Noisy social media influencers chased after the attention, and news orgs rushed to amplify their hot takes. Musk’s mother even weighed in. Within a week, entrepreneurs at the UFC and the Roman Coliseum offered to hold the match which amplified the story even further. By the time of this writing, if you type “Elon Musk Mark Zuckerberg Cage Match” into Google, there are over 20 thousand stories amplifying the sound and fury. For the most part, it’s noise signifying nothing.

It's not that we shouldn’t be talking about these two men, whose smallest decisions - because they own and dictate the algorithms of influential social media platforms that curate what hundreds of millions of people read - weigh heavily on the production and distribution of news and information. But the reporting should be focused on the ways that billionaire owners determine the distribution of news and steer our cultural conversation. For instance, there is a new law in Canada and similar laws being discussed in Europe that require social media companies like Facebook, Google and Twitter to compensate the actual producers of news content for the ad revenue they generate for these distribution monopolies. This would be great for people to deliberate on.

Instead, such news has been drowned out by hot takes on the cage match featuring headlines like “Elon Musk’s dad Errol says if Mark Zuckerberg beats son in cage match Tesla CEO’s ‘humiliation would be total’” or “Musk-Zuckerberg ‘cage match’ PPV would cost $100, bring in over $1 billion: ‘This would be the biggest fight ever in the history of the world’”

Our Take

This overemphasis on "what the rich are up to" is nothing new but has become especially prevalent in today’s culture where income inequality is at historic levels. Today’s inequality is matched only by the Gilded Age, when America’s original robber barons were monopolizing sectors of the economy and buying up newspapers and news distribution services to control the national conversation.

The excesses of the Gilded Age, however, also inspired the muckraking journalists of Progressive Era press, who knew the vital importance of news in a functioning democracy for holding the rich accountable. They saw public interest journalism as the only way to balance the oversized influence of Gilded Age plutocrats. And they were acutely aware of the way that most news orgs tended to focus readers’ attention on the rich.

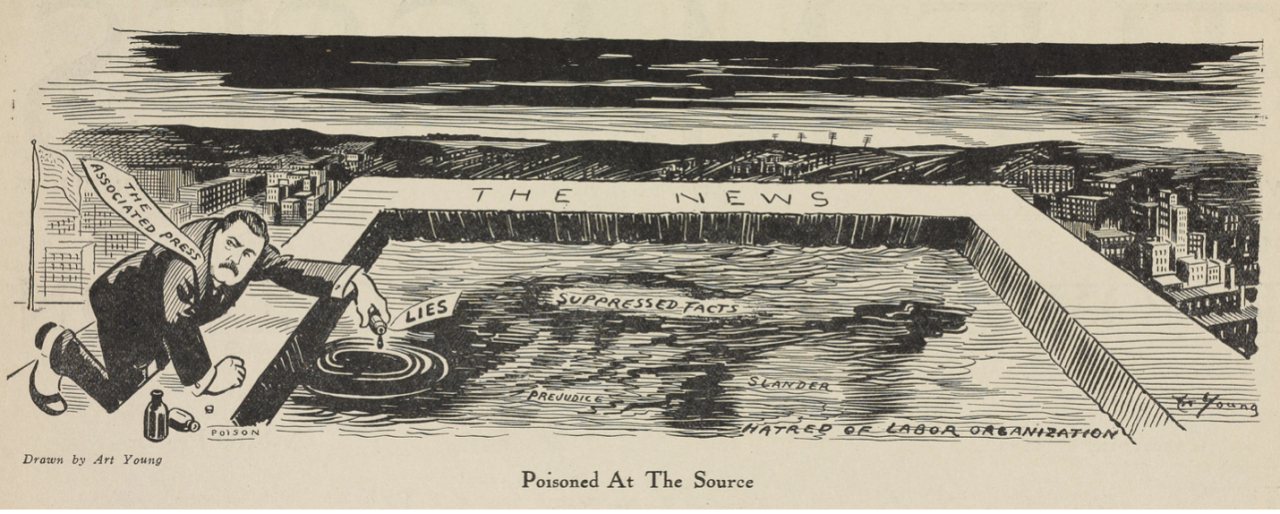

One of the most pointed critics of this news bias was editorial cartoonist Art Young, who got his start illustrating news stories for Chicago’s Evening Mail, Daily News and Tribune. He quickly gained a following and by the 20th Century, he was drawing editorial cartoons for news periodicals with massive circulation like Life, The Saturday Evening Post and Puck. As someone whose work often commented on the priorities of news orgs, he became increasingly critical of their tendency to print stories about the rich and famous and he lampooned the mainstream press repeatedly for it. In 1912, after drawing a cartoon for The Masses that accused the Associated Press of poisoning the “The News” well through their coverage of coal mining strikes West Virginia, the AP used their political power to get him indicted for criminal libel. The AP eventually had the charges dropped to avoid discovery.

A 1912 political cartoon drawn by Art Young and published in The Masses accused the Associated Press of poisoning the “The News” well through their coverage of coal mining strikes West Virginia, and prompted the the powerful AP to press charges.

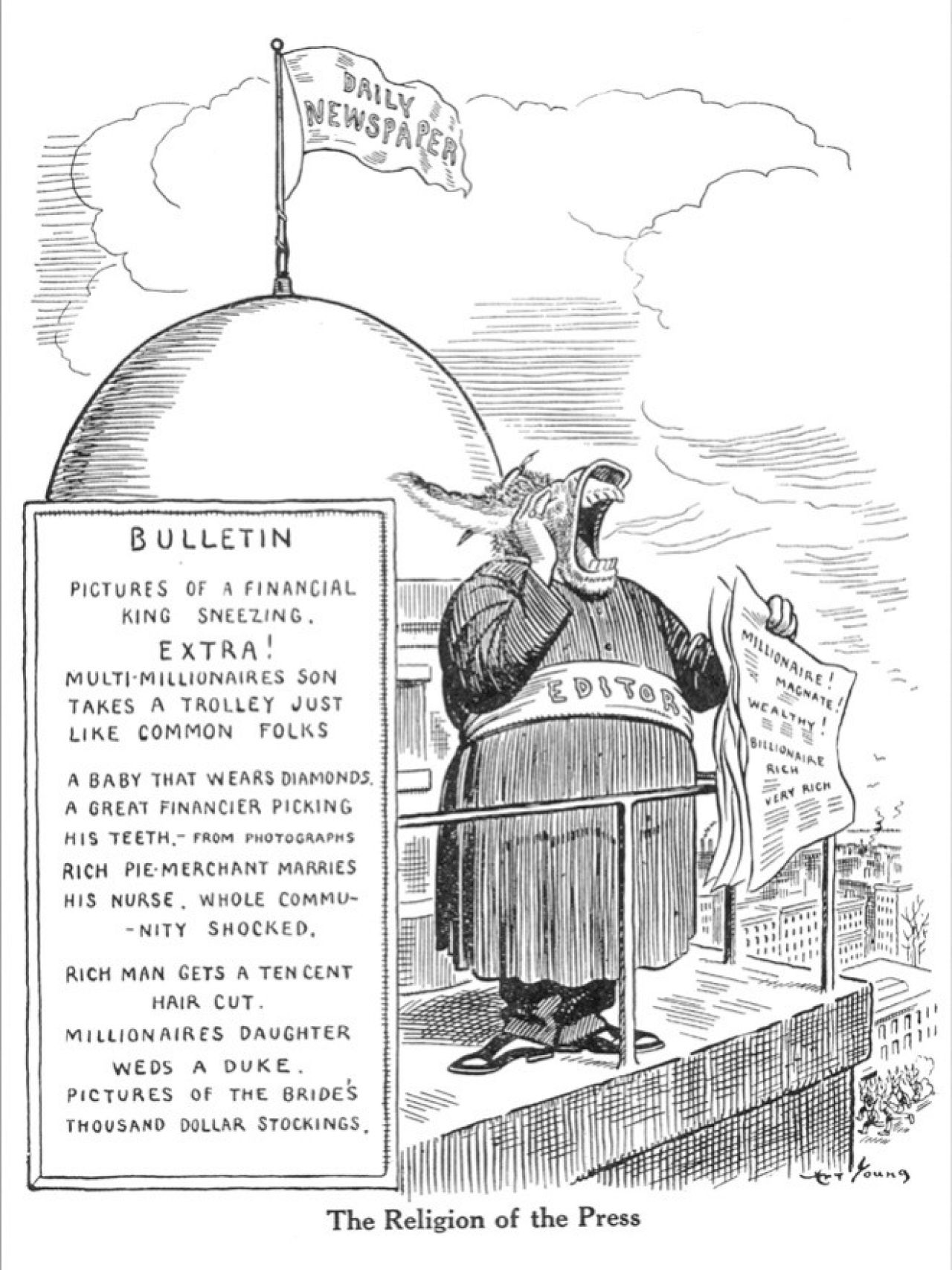

Credit: Art Young, The Masses ( Vol. 4, No. 10 ) July 1913But as much as Young accused the press of sins of commission, it was the sin of omission that continued to haunt his cartoons about the news. In 1920, Young drew a cartoon for his own publication, Good Morning, entitled “Religion of the Press.” It portrayed a braying donkey labeled “Editor” screaming out headlines from the roof of “The Daily Newspaper.” Take a look at the cartoon, which suggests that pictures of “Financial King Sneezing” or stories on how “multi-millionaires Son takes a Trolly just like common folks” dominate the news ecosystem.

In 1920, Young drew a cartoon for his own publication, Good Morning, entitled “Religion of the Press.”

Credit: Art Young, Good Morning, Jan 1, 1920.Thinking with this image about the “Zuckerberg Musk Cage Match” story, it's striking how little editorial priorities have changed. This “religion of the press,” one that privileges stories of the privileged over stories about issues that impact the lives of everyday people, is still guiding the choices editors make every day. Indeed, many news organizations literally have a tab on their online sites that aggregate their stories on “rich people.” When our press focuses on the lifestyles of the rich and famous – and paparazzi armies are always there to take and sell pictures of everything they do - that’s what we-the-people focus on. Positioned as spectators, our conversations tend to be about what the rich are doing instead of what we are going to do as actors. By omitting coverage of issues important to solving the problems we share as a democracy, news orgs further erode our faith in our democratic capacity to deliberate and act.

To us, the “Zuckerberg Musk Cage Match” coverage is mostly noise, showing by their deeds that faithful editors in our news system are still focusing news coverage on the wealthy. Stories about the rich, mind you, are not intrinsically damaging to democracy. They can provide opportunity to highlight inequality and the abuse of power conferred by wealth, both important functions of the press in a democracy. But when stories about the private lives of the rich draw attention away from important public issues, the sins of omission become more pernicious. The noise about the conspicuous consumptions and actions of the rich obscures the democratic signal.

Contact

News Literacy Initiative

newsliteracy@psu.edu