- Episode 109

Protecting Public Interest: The Role of Regulation in Media

Who owns the news? Media buyouts and mergers have become so commonplace you might not even realize that your local paper or news station is owned by a massive corporation in some far-off place. You might think, “I’m still getting access to information, so why does diversity in media ownership matter?” To find out, we talk with Michael Copps, a former commissioner for the Federal Communications Commission.

-

Leah Dajches: In 2011, Comcast merged with NBCUniversal. Former FCC commissioner, Michael Copps, was the lone dissenter on the decision to approve the merger. In his position statement, Copps used powerful language to convey his feelings. He writes, "Comcast acquisition of NBCUniversal reaches into virtually every corner of our media and digital landscapes and will affect every citizen in the land. It further erodes diversity, localism, and competition, the three essential pillars of the public interest standard mandated by law." He ends the statement by calling the merger damaging and potentially dangerous. Wow. The question of who owns the news has serious implications for the quality of journalism we have access to. Media mergers are assessed on business terms, not democratic ones. Any media outlet that is financed by advertisers needs to turn a profit. From that framework, it's not hard to see that financial decisions can end up driving editorial ones. Because of this reality, critics argue that when control over the media is concentrated in fewer and fewer hands, it becomes easier for owners to amplify propaganda driven by their own political views or business interests, thus ignoring the public interests and eroding the quality of journalism.

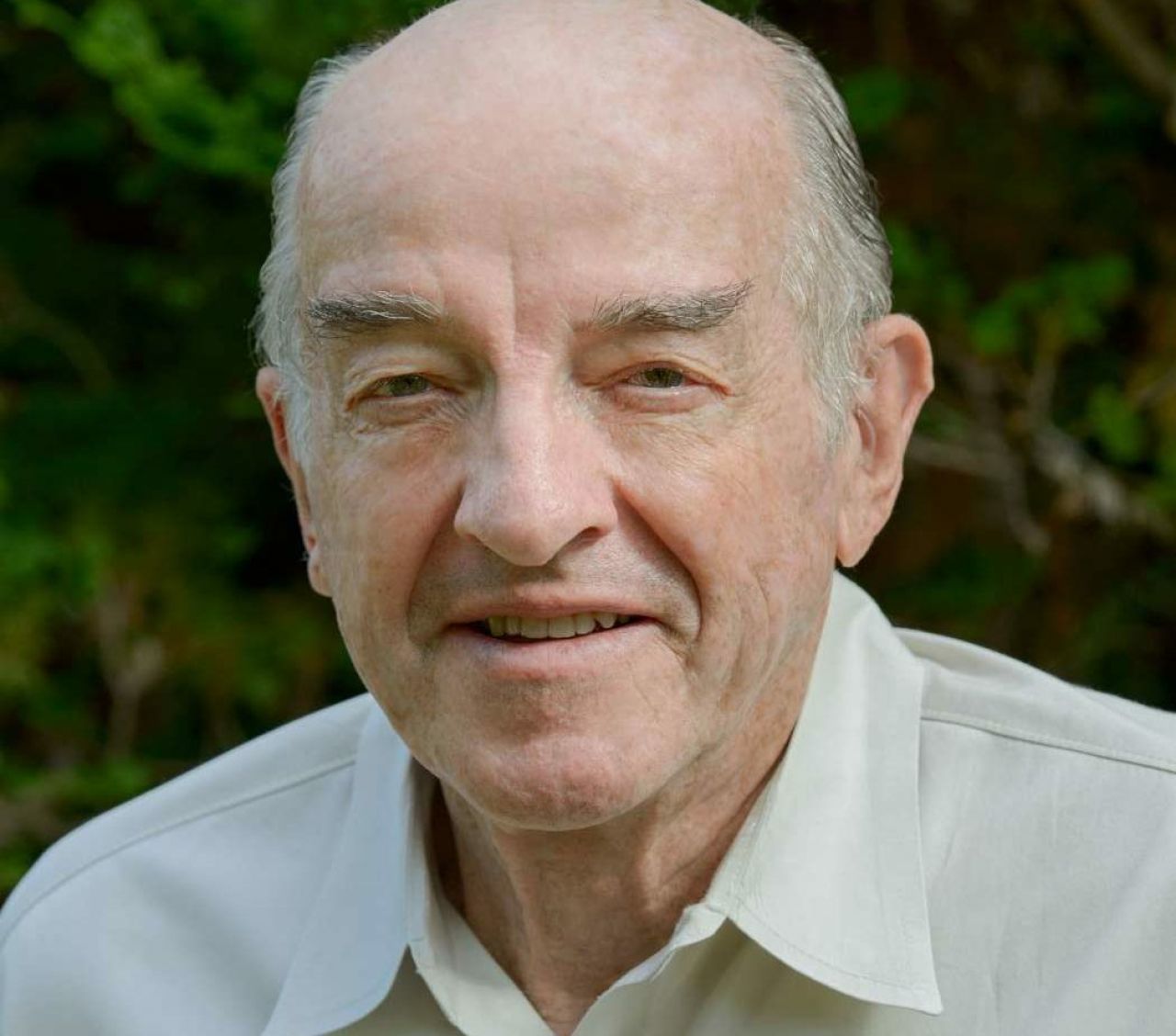

Matt Jordan: Even beyond the precarious relationship between advertising dollars and editorial integrity, these media mergers can have more subtle consequences for news reporting, especially at the local level. As Leah mentioned, these types of decisions are driven by profit, and the pressure to reduce cost can often result in cuts to newsroom staffing, as well as pressure to produce commercially friendly stories. And as news outlets become under-resourced, it makes it harder for journalists to sustain quality professional practices like careful background research and diverse sourcing and topic selection. All of this can have a profoundly negative impact on the quality of the news. But what can be done about it? To find out, we're going to talk with Michael Copps, a former commissioner for the Federal Communications Commission. His tenure was marked by a consistent embrace of the public interest. Copps has been a proponent of localism in programming and diversity in media ownership. Though retired from the Commission, he's maintained the commitment to an inclusive, informative media landscape. Copps currently serves as a special advisor for Common Cause's media and democracy initiatives.

Leah Dajches: We also have another special guest joining us on this episode. Sydney Forde is a PhD candidate at Penn State's Donald P. Bellisario College of Communications. Sydney was recently nominated as the first student member to join WPSU's board of representatives. She's been closely involved in the development of Penn State's news literacy initiative that this very podcast is housed under. Hi, Commissioner Copps. Hi, Sydney. Welcome to the show.

Michael Copps: Thank you very much. Thanks for having me on the show. I am delighted to be here.

Sydney Forde: Yeah, great to be here.

Leah Dajches: So Commissioner Copps, our listeners may not know much about the FCC. Can you tell us a little bit about how it was created in the first place and what it accomplished?

Michael Copps: Well, it goes back a ways to 1934. Actually, there was a radio commission before that in 1927. But basically, the FCC is an independent regulatory body consisting of five commissioners nowadays. The number has varied from time to time. Three would be from the majority party that controls the White House and two would be from the minority. Right now there are three Democrats and two Republicans. Most of the time that I was there, except for a few years, it was three Republicans and two Democrats, so I was doing some holding action. But the Commission was established to bring some order into the communications ecosystem as it then existed to conduct some public oversight over all communications by radio and wire. That would've included primarily then radio and telephones, but later expanded to all of those things that use radio and wire, and to me, that's just about everything. From the standpoint of telecommunications, the idea was that the commission should work to make advanced telecommunications available to the widest possible section of the United States, to everybody really, at reasonable and comparable prices to ensure competition, to protect consumers. It deals nationally. Also deals in international negotiations. It grants licenses to stations and licenses for the airwaves, which all belong, by the way, to the public. No company owns an airwave; airwaves are owned by the people of the United States of America. So it has a lot to do from the standpoint of protecting consumers. It mentions the term "public interest" 116 times. I had my staff look this up when I was at the Federal Communications Commission. By public interest, I think they mean... That's what I said with regard to telecommunications: getting the most advanced out to the most people possible; reasonable, comparable prices; to present programs of public interest and public importance, news and information. So it's a pretty busy little commission. Unfortunately, it's been operating in the last two years with only four commissioners instead of five. So the Democrats do not have a majority, even though they have a right to have the five commissioners. But the Republicans and a couple Democrats too have held up the nomination of the person who has been put forward to be the fifth commissioner. Her name is Gigi Sohn. We keep pushing for her to get confirmed by the Senate so she can take her place at the Commission and get on with the business of doing some transformative things for our communications ecosystem which they are badly in need of, and top of that list is the news and information challenges that our society is facing right now.

Matt Jordan: You once said that the FCC is one of the most important agencies no one has ever heard of, and it might be surprising to our listeners that so many of these things are going on right now. Why do you think we don't as a public hear much about what the FCC does?

Michael Copps: Well, some would say it's because for many years it was a captured agency, beholden to the special interests and to big money. Another reason, which I found out when I got there back in 2001, was it didn't get out of the city much. It held its hearings, monthly hearings or whatever, inside Washington, D.C. And as a result, most people around the country didn't know what the FCC was doing, and just as bad, the FCC didn't know what a lot of people around the country were thinking about either. So I made it one of my goals at the Commission to try to get hearings going, town hall meetings all around the country, and I was pretty successful in that. Not as successful as I would like to have been by getting the policy changed, because I was most of the time in the minority. But in bringing these issues home to the American people so that they can understand that the decisions that the FCC was making actually affected their lives. And from the FCC standpoint, I'd like to get them out of town so they can see what really is concerning people or bugging people or bothering people back home. They're so used to sitting in their nice offices at the FCC and receiving beautifully wrapped ex parte filings, which are things that big business wants from the FCC, and communities like Native Americans or handicapped Americans or all sorts of different Americans never had an idea what was going on. So I wanted to bring these issues up, make them a public issue. And I remain convinced until this day in 2023 that you're never going to get the kind of reform that our telecommunications and media system needs until the pressure comes from the grassroots. And I'm convinced people at the grassroots understand things are wrong, but media doesn't tell them too much about it because media is afraid its own ox is going to get gored. So that's why I think it's important to get out there, get the grassroots going, get some of these changes made while we can still save this democracy of ours.

Leah Dajches: You just mentioned a type of reform. What exactly would the media reform look like?

Michael Copps: Oh, yes. How long do you have here? Well, let's start off with, I guess, what ails it. I think since before the time I got there... When I got there, I thought, "Boy, this is going to be the coolest job in town. I'm going to be dealing with all these high tech technologies that are changing our society and getting broadband out to people and meeting with all the leading lights of the technical world and all that." And I quickly found out that I was going to be spending more of my time meeting with CEOs of radio and television and telephone and cable companies who were there to see me to approve their most recent merger. And there was a majority at that time for mergers; the Commission approved a whole lot of mergers. So, the industry consolidated. Local community stations were bought up. Many were closed down. Many just became part of a much larger national media organization. So they corporatized. They lost touch with the communities. Main offices sometimes were moved to places like New York or big cities. And then the corporations really, to my mind, got in the business of thinking about news and information as entertainment for the American people. And goodness knows, we've gone too far down that road. Politics has become a spectator sport rather than a participatory sport most of the time. We maybe lost half of our newsroom employees or more. Figures vary from source to source, but we've probably lost the last 20 years half of our newsroom workforce. We've closed up so many stations, couple of thousand newspapers, daily newspapers, and weekly newspapers. And to my mind, when you have a journalism that's consolidated like that and closing up local bureaus and you don't get the coverage of the local education or the mayor's office or the health board or the state capitols... Lots of state capitol coverage was cut back, and more legislation gets passed at the state level than in Congress, which is incapable of doing almost anything most of the time. When people like the information that they need to make intelligent decisions about the future, bad things happen. And goodness knows enough bad things have happened in this society of ours over the last 20 or however many years you want to say, that I worry for the very survival of democracy. And it sounds easy to say, but I'm very serious about it. If you don't have that informed electorate, you are really playing with fire. I always carry around this little quote here from James Madison, who said "A popular government without popular information or the means of acquiring it, has been a prologue to a farce or a tragedy, or perhaps both." And then he went on to say, "People that mean to be their own governors must arm themselves with the power knowledge gives." And we're not doing that right now. We have to get a media system that digs for real news, that informs, rather than just entertains, that builds new outlets and facilities, figuring out how to use the internet much better for our news. So we've got lots to do. And I think to do that, we need a return to regulation, public interest oversight. I mentioned it appears 110 times in the Communications Act, congress mentioned something 110 times, I tend to think that they were serious about it. So I think we have the wherewithal, but that communications act that I talked about has been seriously undermined over the years because of captured regulators, because of the ideological changes that we underwent during the presidencies of, starting with Ronald Reagan, and then George W. Bush, and all the rest. So we've got a ton of work to do. We can go into more details, but that's the umbrella that I see. We've corporatist consolidated and cable-ized our media, and lost the art of real journalism in the process. Not that we ever really had a Golden Age of media, but with the tools that we have available to us now, maybe we should have. I mean, we were all excited when that internet came along. My goodness, that was going to be the new town square of democracy. Power at the edges, and everybody would have a voice, and compare that with the reality that evolved, with power consolidated in the middle, and a few big companies controlling our internet experience. So, you can see the opportunity that we have missed, and which should have been a golden opportunity. It turned out to not be quite the opposite.

Matt Jordan: So, when you were sitting in that chair, when you were meeting with the CEOs and whatnot, what would they be arguing for in opposition to the public interest? What interest did they think that they were serving, that they wanted to supersede the Democratic Public Interest Initiative?

Michael Copps: Well, what they wanted me to believe was that they could be much more efficient. They would have all these economies of scale and everything, and they would be able to do a better job of producing the news, and informing the people. In reality, what they wanted to do was make a bigger impression on Madison Avenue, and Wall Street, and build up the power of their stock holdings and make a lot of money. But they wanted me to believe that they were serving the public interest. And I'm not saying that each and every merger was necessarily bad. You could find cases and when we did, I would support them, when the community really did have to combine a couple of stations in order to have anything at all. But that was the rarity, more than the regularity.

Sydney Forde: Clearly, a lot of your work, while at the FCC, was grounded in this deep concern on how to make sure that the American media environment supports a healthy democracy, as we've been talking about, specifically with this focus on diversity of media ownership. So what is the FCC's role here, in intervening in anti-competitive media mergers, as compared to other government agencies? We often think of the FTC when we're talking about anti-trust, and things like that. So what really is the FCC's-

Michael Copps: Right, well, the FCC does have a role to play in anti-trust, along with the FTC, and the Department of Justice. From the standpoint of protecting the public interest, protecting consumers, and doing the things that are laid out in the Communications Act, so it can disapprove of those mergers. The merger that I thought would change everybody's mind was when Comcast and NBC Universal came along, and here was a merger I said to myself, now everybody's going to see what's involved here. This is horizontal consolidation, and vertical. This is two companies that will control both the content and the distribution of media. If that's not a definition of monopoly, I don't know what it was. Plus, as I said in my statement at the time, this is just too big. No company in our country, in a democracy, should be allowed to wield this much power. I was the only commissioner that voted against that merger. I'm proud of that. Well, I'm convinced more than ever that it was the right vote, but I thought that would open up everybody's eyes and they'd say, "Oh yeah, we see where this is going now. This is old media and new media, and everything's going the way of radio and television." But they didn't see that. And of course, these companies spend tons of money advertising. They spend even more money on lobbying the Hill, and even more money than that in contributing to congressional candidates. So they don't have a lot of trouble getting their message across, and that's what we have to deal with. It's a story that the American people, they have a feeling something is wrong. I went around the country as a commissioner, and after, when I went to Common Cause holding town hall meetings. And people would turn out, and lots of times these meetings would go on to 12, one, and to two, two o'clock in the morning. And you could tell people were upset, but they hadn't really understood all the reasons why what was happening, because the big media didn't want to tell them, because they would pay the price if the people rose up and demanded reform. It was interesting when I'd go around to these cities and towns, if I went to a place that still had some semblance of independent media, independent TV, and radio, and newspapers, where they'd print a little article before the FCC got there, and I usually had at least my Democratic colleague, and a few times that the big media would write, say, you're coming to town. When you got there, they would cover the hearing on television, and then when you left, they'd write an article summing it up. If you went to a town where Consolidated Media was in control, what you found was no much, unless you were coming to town, or maybe a little bit, no live coverage, and nothing summing up what had happened. It's interesting, I'll tell you another story. I went one time to the editorial page editor of the major East Coast newspaper, and while I was sitting in the waiting room, waiting to meet with this person, I wrote a story on that day's editorial page of the paper there, "Stop Big Oil" it said, so the editor came out and I said, "Hi, I'm Mike Copps. I'm here to get you to write one of these that says 'Stop Big Media.'" That person looked at me and said, "Oh no, I cannot do that. I have free rein to cover whatever subject I want, except one, and you just named it." Here I almost fell of my chair, as a sitting commissioner at the Federal Communications Commission, and that person was being very, very direct with me. I appreciated her candor, but I was shocked by it, too.

Matt Jordan: Does it surprise you that public media doesn't promote the good work of the FCC more? That public media-

Michael Copps: Well, it does give us some money. The longer I look at this problem, I'm convinced that commercial media cannot solve its own problems, the commercialized media system, and we either have to find a way out to make the two work together, and enhance public media system, and commercial, or else we just have to go much more towards a public media. We are one of the countries that gives the least to public media in all of the world. We're way, way down in the rankings of, I think we give on a per capita basis something like $3 and 16, or 60 cents per capita, per annum to support public media. Whereas other countries are 60, 70, 80, $80, and we're, we're a big country. We're going to need even more than that. We need to be serious about public media. The only debate we seem to have in the last 20 years I've been watching in Congress is, should we zero this program out, or should we just hold it at the tight budget it's already at. We should be talking about how to get lots more money into it. And particularly that applied to local news, public media does a good job on what it has, but it doesn't do much with local news. We do have the national news and PBS and all, but you got to give it the resources, too, to attract people who are otherwise watching Lester, or David, or whoever on the nightly news, and go to something a little bit deeper. So we have to get serious about that. I don't know how we can do it, I just know that part of any long-term solution is more support for public media. And if it's long-term, I don't even know if it is a solution, it might be too late. But I think I'm interested in restoring regulation where recent FCCs have taken it away. Radio and television, they got rid of a lot of the rules against consolidation, and what you have to do. And licensing went from once every four years, you were supposed to show you're serving public interest, and now it's eight years. And you basically send in a postcard, and they send you a renewed license. And the Ajit Pai, the last Republican chair did away with so many regulations, like the station doesn't have to have its main studio in the community it serves, it can be farther away, and has much easier route to do what's called shared service agreements with other stations. That's where when a station doesn't completely buy another station, but it operates it, and dictates the program, and the list goes on and on. So I'd bring that back for radio and television. I'd find a way to include cable. Cable was not carved out, even though that preamble to that act I talked about at the beginning says everything with radio and wire. Well, cable is radio and wire to me, so is the internet, for that standpoint. So we need to bring back traditional regulation, and then extend it. That's number one. Number two is anti-trust, maybe that's number one, I don't know. Much more rigorous in anti-trust, and breaking up some of these companies. And certainly stopping all these new ones, like we got TEGNA and Apollo One going on right now. Number three is public media, that we've been talking about here. So important. And number four, and if I'm getting too far off the track, stop me. But the only long-term solution, or the really effective long-term solution in all this would be getting serious as a country about media literacy. There is no substitute for that. And for years at the commission. And since then, I have said we need to get right away a K through 12 curriculum up online teaching digital media, if you want to call it that, new media literacy is what I call it, because it encompasses everything. There's enough stuff out there that different schools have put together and even some companies and foundations, and you could spend six months putting that together or less, put it up online. If your local school board didn't want any part of it, all right, let them go their way. But I think there'd be a lot of them that would want to be a part of it. And we've got to teach these kids not just how to use this technology, but who do you trust? How do you find something that you trust? How does technology work? How do you develop new technology? There's something for every grade, at least K through 12, and we ought to be about that seriously. Is that a big order? Yeah, it's a huge order because what you hear, first thing you hear is we've got our STEM programs and we've got to do that, and that's mighty important to the future of the country. And they're right, but so is this media literacy and understanding what's going on in your country so you can perpetuate its democracy. So I'm for that, and I pleaded with the chairman to... Let's get the public sector and private sector in and let's see what they've got that we can make quick use of, and get something going online, and then work together. Maybe it'll just be the public sector that does it. I wanted to get education involved along with the Federal Communications Commission, but that hasn't come to pass yet. So we're talking more now about the media. We've accomplished, I guess that much and it's at least a subject of discussion. But that's as far as you can get with this Congress that we have now. And now we have a Supreme Court that seems poised to go off in an opposite direction. And just to be very frank, you worry about the future of all independent agencies and federal agencies right now because there may be a majority on the court. There's certainly a number of people who are saying, "Oh, those independent agencies, that goes beyond what the Constitution allows.” And if Congress wants something done, it has to put every little dot, tittle in every piece of legislation for it to pass muster. But how can that happen when you're doing these 7, 800, 900, 1000, 1,500-page pieces of legislation, that most congressmen don't see until the day before they vote or the day that they vote and they don't have time to digest. But there's something called the Chevron Doctrine. I don't want to get too deep into the weeds, but it's established by the court and it basically says where a law or a statute is ambiguous, that the agency has maneuver room to interpret that law and design what it says, and that's what most of these agencies do. If that power was taken away, we'd be left to an even deeper hole than the one we're in right now.

Sydney Forde: Just a reminder, this is News Over Noise. I'm Leah Dajches.

Matt Jordan: And I'm Matt Jordan.

Sydney Forde: We're talking with Michael Copps, a former Commissioner of the Federal Communications Commission about the role of regulation in today's media. We're also joined by Sydney Forde, a PhD candidate at Penn State's Donald P. Bellisario College of Communications.

Matt Jordan: One of the things that the Chevron Doctrine might've been implied to is this notion of the public interest. When you were at the FCC, did you have deliberation where you talked about things like when people would have to re-up their license? Did you talk about is this station serving the public interest? Did you have a criterion that you evaluated whether the media corporation was serving that aim?

Michael Copps: Well, the commission has tried that before. I mean, they had generally, "Are you doing a good job? Are you serving the public interest?" They had things like, it was called the Blue Book, 1946, the Blue Book and the Truman Administration into the Roosevelt, beginning of the Truman administration. And it said stations should put limits on advertising. They should have children's programs. They should reflect the economy of the area they serve. They should respect and cover the diversity of populations that exist in that area, public events. Some of the programmers should be locally produced rather than brought in from without. But when that came along, the Blue Book, the broadcasters basically red-baited it out of existence. That was during the beginning of the Un-American Activities and the McCarthy period, and all of that. I have proposed different elements for that. I think licenses should be eight years instead of four years. And I think there should be an examination. "Are you serving the public interest? Are you doing some of these things?" Put them back. Well, they were never really into effect, but at the beginning though, when the FCC was new, I think companies took it more seriously because it was new legislation. It was coming out of the New Deal and all of that, and they were afraid if they went too far afield that something bad would happen. But the years went on and agency didn't seem to be doing that much damage to them and was actually approving some of their mergers and acquisitions and all of that, so they got a little less afraid of it. By the way, all these things I'm talking about may apply to some extent in telecommunications too, and the internet service providers, broadband providers. Because another thing that I watched was consolidation in the telephone industry. The Bells wanted to get in long distance, AT&T wanted to get in, and they really distorted the rules. There were some decent rules in the Telecommunications Act that prevented all that, but they worked around that with some friendly commissions and all that. So that's why we've had all that consolidation in telecom with the big telecommunications companies like Verizon and AT&T and the others.

Matt Jordan: We often talk, and when we're thinking about making the news better, I think people like the idea of having a referee out there. Somebody's going to keep people following the rules. Would you like to see something like the Fairness Doctrine brought back into some kind of serviceable form? The Fairness Doctrine, which demanded equal time for different points of view and demanded a lot of different perspectives in the service of the public interest.

Michael Copps: Well, I wish we could, I don't know if we can. We need something like that. I mean, the mini-ecosystem has evolved so much with all of these cable shows and everything like that now. But the Fairness Doctrine wasn't so onerous to begin with as the broadcasters would have you believe. We weren't in a straight jacket because of the Fairness Doctrine. There weren't that many cases brought against them. It didn't cover all viewpoints. It didn't demand a lot of the stations. So I don't know what you can do. We have to do something to protect the public interest. The Fairness Doctrine was an attempt to do that. We need to be creative in thinking, are there other things we could do? Could we maybe somehow demarcate between news stations and opinion sessions and put it on different places in the dial or something like that? I just thought of that the other day. I don't know what the cons of that would be, but I'm sure that there would be some, and it'd be one thing you could do. Maybe you would figure out a way that there would be licensing and just some kind of generalized public interest standard. The more specific you could make it, the better I would like it. But something that would make radio, TV, and cable more responsive to balanced reporting. You can't save democracy when we're just shouting opinions at each other rather than digging for facts and letting journalists do their job, and find their way through this mess that we're in. I think if you had a good public system that would help a lot too, maybe that would raise people's expectations. But yes, I would like to see something like that. But we have to be cognizant of the fact that it's probably a little more difficult to do now, but that doesn't mean it's impossible to do. And I've just been saying for years and years and years, every time a new president comes in, why don't we just have a really top level, really impressive commission, it doesn't have to be an agency, commission for a year or two to take a look at this? We did this during the transition to digital TV that was the so-called Gore Commission and looked at the public interest obligations of broadcasters in the digital age. But I think if we had a really blue ribbon panel that looked at all the problems of the internet and the media system generally, had a White House sponsorship, so it had visibility and the press would have to cover it, and we could engender a national discussion. We don't even know all the questions to ask. We sit around here and argue, "Well, all we need to do is fix Section 230," or do this or that. That's not true. I mean, what you have to do is take a holistic look at our media, artificial intelligence, algorithms, privacy, all these other things, consolidation, and try to come up with a report with some recommendations, and then the commission can go out of existence, or do whatever to decides it should do. But we would at least have had a national discussion. As I said before, I think the national discussion is a prerequisite for a national action on it, but I haven't been able to get that yet. So I'm encouraged by the number of columnists now they're beginning to write and journalists a little bit more about media, but I don't see much leading toward action right now, and that's what we need to do. So I'd like to see people running on this. I'd like to see more people covering it. And I guess it was one of my predecessors, Nick Johnson at the Federal Communications Commission back long before I got there, he said, "If media reform is not your number one issue, maybe your number one issue is the environment or the economy, or health or LGBTQ, environmentalism, disabilities communities, racial diversity, women's rights, labor rights, those are all important, but if that's going to be your number one issue, you better make sure that this media reform is your number two issue, because those number one issues aren't going anywhere until we reform our media."

Sydney Forde: On that point, I mean, clearly in our discussion here, we're focusing on the importance of the FCC when it comes to journalism, when it comes to news, and I guess going back to your earlier points, talking about sort of the stalling of [inaudible 00:33:04] nomination. Could you speak a little bit more to just, in simple terms, what's going on with that and how it's impacting the FCC's ability to make these important decisions and really why everyone should care about this?

Michael Copps: Well, what's going on is just a political battle royal. Some people think that maybe [inaudible 00:33:23] is a little too opinionated or a little too liberal for them. I don't know. We've had liberal and opinionated discussions before. They had me there for a while. I was occasionally opinionated. But anyhow, I think it's special interest. It's big money. The industries have poured millions of dollars into lobbying against her nomination right now. And the industries are important when it comes campaign time, and Republicans are ideologically disposed to be against her, but letting an independent agency like that vacant for over half of a presidential term is just a shocking. It's supposed to be doing a job with five votes. The current chairwoman, Jessica Rosen Wersel, who used to work for me, brilliant, she's done a great job with a two commission on broadband and Lifeline and several other things. But I want her to be a really transformative chairperson of the FCC and do things on media consolidation, on network neutrality, on privacy, and on all these other things that help can help restore our media ecosystem. But Congress has not let that happen, and I hope it'll happen pretty soon, but they keep putting the vote off. They've had two complete hearings for a [inaudible 00:34:46] before the Senate Congress Committee in the last Congress. They shouldn't need any more. But now the Republicans all say, "Oh yeah, we have to be done. We have to start from scratch, start all over, more hearings, more weeks, more months." So it's depressing. It makes government dysfunctional and she would do a good job there. As I said, I think the campaign they're running against her is somewhat sickening and it's should be embarrassing to them, but it's not. But it's embarrassing to our democracy that we can't find a way around that. So I hope that the president will push that really hard. I hope that the majority leader of the Senate, Mr. Schumer will say, we're going to vote on this and bring some pressure to bear on people who haven't made up their minds yet and let's get it done and get on with the business while we still have some time.

Leah Dajches: So we've talked a fair amount about potential solutions and I'm trying to think more at the individual level for our listeners out there, kind of what I'm taking away is that a lot of these decisions about media ownership and consolidation are being made for us, and you suggested that media literacy could be a potential solution for our everyday citizens. But is there anything else that you can give to our listeners about how we can engage with the FCC or try to improve fairness in the media?

Michael Copps: Well, to me, if you look back over the course of American History, reform has seldom come as a gift from this wonderful leaders and politicians in Washington. It's usually come in response to pressure from the grassroots, whether you're talking about abolition or civil rights or women's rights or labor rights or disability rights, indigenous [inaudible 00:36:33] goes up and down the whole line. That's how you get their attention and their vote. I remember a congressman called me one time when I was at the FCC and he had not been friendly toward what I was trying to do up in the hill at that particular time, and he called to say, "I never thought that this media consolidation issue is really a very big deal." He says, "I went home last week and I had a town hall meeting and hands went up all over the place and people were talking about the state of the media. I was really surprised. The guy came back and voted with me at the Federal Communications Commission." That's just an example of how I think it works. So yes, it's got to come from us and not going to come from up on top, I don't believe, unless we get a really visionary communications person, a communications democrat, small D, in there, it's going to come from pressure from back home. So you talk to your family, you talk to your college roommate, you talk to your friends, you talk to your business colleagues and just try to make people aware of the issue that's out there. You write a letter to the editor if the newspaper will publish it or try to go out and talk radio if they don't boot you off from the right wing. But you do whatever you can to get the word out there and you're organized. That's why we have groups like Common Cause where I spend some time and pre-press and labor unions and others. We've got to make it an issue, an issue that's covered and an issue that people can understand better than they do right now and then you'll get changed. And time is not, in my mind, unlimited for us to do that. I don't think we can afford to take our time. I think our democracy deteriorates every day.

Matt Jordan: You're describing talking to the congressman who came to you and him having a kind of an epiphany, and what would you say to people out there who might think, because they've been told to think this for years, that deregulation makes everything more efficient and better for the consumer. You've been watching this for decades. What would you say to counter that belief or that myth that deregulation is always good for consumers?

Michael Copps: Well, I'd say how do you think our airlines are doing and how do you think our hospital and healthcare system is doing? And you can probably go up and down the line, and Lord knows I'm not for the heavy hand of government to stultify anything but I am [inaudible 00:39:11] of government to protect the public interest. That's what our country was all about. That's what the Constitution is all about. That's what the Telecommunications Act was all about. You can't just let everything go willy-nilly in a society where if you do big money and special interests are going to control everything, the people have to be in ultimate control and it's empowering them. It's their government. If they don't like it the way it is, we can change it, but the government's not the enemy. Government is us, and it's got to be the people working together. As I say, time is wasting.

Matt Jordan: Well, speaking of time, we're about out of time, so Commissioner Copps, I'd like to thank you so much for being with us and sharing some of your experience and some of your wisdom with us in our audience.

Michael Copps: I enjoyed it. I enjoyed your questions. I really am appreciative of the fact that you all are covering the issue and trying to get word out there and happy to talk to you guys anytime and it's a pleasure being with you this afternoon.

Matt Jordan: That was a really in interesting conversation, and it's so good to hear from somebody who's had so much insider knowledge and with so much experience and who's tried for so long to make the media system more fair. It reminds me, there's a great quote from him that I think summarizes a lot of what we've been talking about on this show, that it's a democracy runs on information. Information is how we make intelligent decisions about our future and how we hold the powerful accountable. Deprive citizens of relevant, accurate, and timely information, and you deprive them of their ability to govern themselves. And that makes me think that what he's talking about in terms of media reform is so important. Leah, what were your takeaways?

Leah Dajches: I have two big takeaways, and I think that's really, as citizens and media consumers, we shouldn't feel helpless. Commissioner Copps was talking about how a lot happens at the grassroots level. So it's talking about it. It's talking about what is going on in the FCC, who is owning our media and our news stations. And I think that to me kind of also really emphasizes the importance of media literacy. And I know I'm biased, but I also can't stress enough hearing it from Commissioner Copps that having media literacy taught in schools. It's something maybe you talk around with your family is vital, I think, for the health of our democracy in our media inundated world.

Matt Jordan: And Sydney, you've been thinking about these issues for a long time. What do you think?

Sydney Forde: Yeah, I think it was so great to talk to Commissioner Copps today and really hear from him. This emphasis on the role of the FCC and really it makes me think of in this sort of crazy sensationalized news environments that we're all so familiar with that of course is driven by the news organizations, sort of as Commissioner Copps was saying, need for profit, how do we get people to think about these really important issues? The fact that the FCC has not been running, essentially operating, how it should for two years now is something that all Americans should be concerned about. So I think that finding out how to really get everyone engaged so that they can, as Leah was emphasizing, get involved and really make a difference is really a big question.

Leah Dajches: That's it for this episode of News Over Noise. Our guest was Michael Copps, a former commissioner for the Federal Communications Commission. We were also joined by Sydney Forde, a PhD candidate at Penn State's Donald P Bellisario College of Communications. For more on this topic, visit newsovernoise.org. I'm Leah Dajches.

Matt Jordan: And I'm Matt Jordan.

Leah Dajches: Until next time, stay well and well informed.

Matt Jordan: News Over Noise is produced by the Penn State, Donald P Bellisario College of Communications and WPSU. This podcast has been funded by the Office of the Executive Vice President and Provost at Penn State and is part of the Penn State News Literacy Initiative.

END OF TRANSCRIPT

About our guests

Michael Copps is the Special Advisor for Common Cause's Media & Democracy initiatives where he provides guidance on the program's work to promote an open and accessible media ecosystem. From 2001-11, he served as a commissioner of the Federal Communications Commission, where his tenure was marked by a consistent embrace of the public interest. As a strong voice in opposition to consolidation in the media, he dissented in the FCC vote on the Comcast-NBC Universal merger. He has been a consistent proponent of localism in programming and diversity in media ownership. Though retired from the Commission, he has maintained a commitment to an inclusive, informative media landscape.

Sydney L. Forde is a Ph.D. candidate in the Donald P. Bellisario College of Communications at the Pennsylvania State University studying the political economy of media industries. Specifically, Forde studies journalism as a merit good, and broadband infrastructure as a public good, while advocating for public media and municipal broadband (respectively) as non-commercial alternatives to existing commercial dominated markets. She was recently nominated as the first student member to join WPSU’s board of representatives, was a COMPASS fellow with Annenberg’s MIC Center in Washington DC in the summer of 2022, and has been closely involved in the development of the university wide News Literacy Initiative at Penn State. Forde has published articles in the Canadian Journal of Communication, Communication, Culture & Critique, and Journalism, as well as public scholarship pieces in Yale’s Law and Political Economy (LPE) project and The Conversation.